If you are bitten by a venomous snake, call your local

emergency number immediately, especially if the area changes color,

begins to swell or is painful. Many hospitals stock antivenom drugs,

which may help you.

If possible, take these steps while waiting for medical help:

India developed a national snake bite protocol in 2007 which includes advice to:[33]

As of 2008, clinical evidence for pressure immobilization via the use of an elastic bandage is limited.[34] It is recommended for snakebites that have occurred in Australia (due to elapids which are neurotoxic).[35] It is not recommended for bites from non-neurotoxic snakes such as those found in North America and other regions of the world.[35][36] The British military recommends pressure immobilization in all cases where the type of snake is unknown.[37]

The object of pressure immobilization is to contain venom within a bitten limb and prevent it from moving through the lymphatic system to the vital organs. This therapy has two components: pressure to prevent lymphatic drainage, and immobilization of the bitten limb to prevent the pumping action of the skeletal muscles.

Antivenom is injected into the person intravenously, and works by binding to and neutralizing venom enzymes. It cannot undo damage already caused by venom, so antivenom treatment should be sought as soon as possible. Modern antivenoms are usually polyvalent, making them effective against the venom of numerous snake species. Pharmaceutical companies which produce antivenom target their products against the species native to a particular area. Although some people may develop serious adverse reactions to antivenom, such as anaphylaxis, in emergency situations this is usually treatable and hence the benefit outweighs the potential consequences of not using antivenom. Giving adrenaline (epinephrine) to prevent adverse effect to antivenom before they occur might be reasonable where they occur commonly.[39] Antihistamines do not appear to provide any benefit in preventing adverse reactions.[39]

The following treatments, while once recommended, are considered of

no use or harmful, including tourniquets, incisions, suction,

application of cold, and application of electricity.[36] Cases in which these treatments appear to work may be the result of dry bites.

If possible, take these steps while waiting for medical help:

- Remain calm and move beyond the snake's striking distance.

- Remove jewelry and tight clothing before you start to swell.

- Position yourself, if possible, so that the bite is at or below the level of your heart.

- Clean the wound, but don't flush it with water. Cover it with a clean, dry dressing.

Snake identification

Identification of the snake is important in planning treatment in certain areas of the world, but is not always possible. Ideally the dead snake would be brought in with the person, but in areas where snake bite is more common, local knowledge may be sufficient to recognize the snake. However, in regions where polyvalent antivenoms are available, such as North America, identification of snake is not a high priority item. Attempting to catch or kill the offending snake also puts one at risk for re-envenomation or creating a second person bitten, and generally is not recommended.

The three types of venomous snakes that cause the majority of major clinical problems are vipers, kraits, and cobras. Knowledge of what species are present locally can be crucial, as is knowledge of typical signs and symptoms of envenomation by each type of snake. A scoring system can be used to try to determine the biting snake based on clinical features,[31] but these scoring systems are extremely specific to particular geographical areas.

First aid

Snakebite first aid recommendations vary, in part because different snakes have different types of venom. Some have little local effect, but life-threatening systemic effects, in which case containing the venom in the region of the bite by pressure immobilization is desirable. Other venoms instigate localized tissue damage around the bitten area, and immobilization may increase the severity of the damage in this area, but also reduce the total area affected; whether this trade-off is desirable remains a point of controversy. Because snakes vary from one country to another, first aid methods also vary.

However, most first aid guidelines agree on the following:

- Protect the person and others from further bites. While identifying the species is desirable in certain regions, risking further bites or delaying proper medical treatment by attempting to capture or kill the snake is not recommended.

- Keep the person calm. Acute stress reaction increases blood flow and endangers the person.

- Call for help to arrange for transport to the nearest hospital emergency room, where antivenom for snakes common to the area will often be available.

- Make sure to keep the bitten limb in a functional position and below the person's heart level so as to minimize blood returning to the heart and other organs of the body.

- Do not give the person anything to eat or drink. This is especially important with consumable alcohol, a known vasodilator which will speed up the absorption of venom. Do not administer stimulants or pain medications, unless specifically directed to do so by a physician.

- Remove any items or clothing which may constrict the bitten limb if it swells (rings, bracelets, watches, footwear, etc.)

- Keep the person as still as possible.

- Do not incise the bitten site.

India developed a national snake bite protocol in 2007 which includes advice to:[33]

- Reassure the person. Seventy percent of all snakebites are from non-venomous species. Half of bites from venomous species poison the person.

- Immobilise in the same way as a fractured limb. Use bandages or cloth to hold the splints, with care taken not to apply pressure or block the blood supply (such as with ligatures).

- Get to a hospital immediately. Traditional remedies have no proven benefit in treating snakebite.

- Tell the doctor of any systemic symptoms, such as droopiness of a body part, that manifest on the way to hospital.

Pressure immobilization

For more details on this topic, see Pressure immobilization technique.

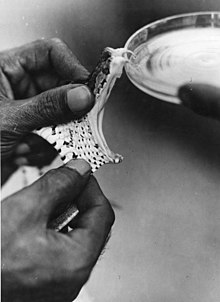

A Russell's viper is being "milked". Laboratories use extracted snake venom to produce antivenom, which is often the only effective treatment for potentially fatal snakebites.

The object of pressure immobilization is to contain venom within a bitten limb and prevent it from moving through the lymphatic system to the vital organs. This therapy has two components: pressure to prevent lymphatic drainage, and immobilization of the bitten limb to prevent the pumping action of the skeletal muscles.

Antivenom

Until the advent of antivenom, bites from some species of snake were almost universally fatal.[38] Despite huge advances in emergency therapy, antivenom is often still the only effective treatment for envenomation. The first antivenom was developed in 1895 by French physician Albert Calmette for the treatment of Indian cobra bites. Antivenom is made by injecting a small amount of venom into an animal (usually a horse or sheep) to initiate an immune system response. The resulting antibodies are then harvested from the animal's blood.Antivenom is injected into the person intravenously, and works by binding to and neutralizing venom enzymes. It cannot undo damage already caused by venom, so antivenom treatment should be sought as soon as possible. Modern antivenoms are usually polyvalent, making them effective against the venom of numerous snake species. Pharmaceutical companies which produce antivenom target their products against the species native to a particular area. Although some people may develop serious adverse reactions to antivenom, such as anaphylaxis, in emergency situations this is usually treatable and hence the benefit outweighs the potential consequences of not using antivenom. Giving adrenaline (epinephrine) to prevent adverse effect to antivenom before they occur might be reasonable where they occur commonly.[39] Antihistamines do not appear to provide any benefit in preventing adverse reactions.[39]

Outmoded

Old-style snake bite kit that should not be used.

- Application of a tourniquet to the bitten limb is generally not recommended. There is no convincing evidence that it is an effective first-aid tool as ordinarily applied.[40] Tourniquets have been found to be completely ineffective in the treatment of Crotalus durissus bites,[41] but some positive results have been seen with properly applied tourniquets for cobra venom in the Philippines.[42] Uninformed tourniquet use is dangerous, since reducing or cutting off circulation can lead to gangrene, which can be fatal.[40] The use of a compression bandage is generally as effective, and much safer.

- Cutting open the bitten area, an action often taken prior to suction, is not recommended since it causes further damage and increases the risk of infection; the subsequent cauterization of the area with fire or silver nitrate (also known as infernal stone) is also potentially threatening.[43]

- Sucking out venom, either by mouth or with a pump, does not work and may harm the affected area directly.[44] Suction started after three minutes removes a clinically insignificant quantity—less than one-thousandth of the venom injected—as shown in a human study.[45] In a study with pigs, suction not only caused no improvement but led to necrosis in the suctioned area.[46] Suctioning by mouth presents a risk of further poisoning through the mouth's mucous tissues.[47] The well-meaning family member or friend may also release bacteria into the person's wound, leading to infection.

- Immersion in warm water or sour milk, followed by the application of snake-stones (also known as la Pierre Noire), which are believed to draw off the poison in much the way a sponge soaks up water.

- Application of a one-percent solution of potassium permanganate or chromic acid to the cut, exposed area.[43] The latter substance is notably toxic and carcinogenic.

- Drinking abundant quantities of alcohol following the cauterization or disinfection of the wound area.[43]

- Use of electroshock therapy in animal tests has shown this treatment to be useless and potentially dangerous.[48][49][50][51]

Caution

- Don't use a tourniquet or apply ice.

- Don't cut the wound or attempt to remove the venom.

- Don't drink caffeine or alcohol, which could speed the rate at which your body absorbs venom.

- Don't try to capture the snake. Try to remember its color and shape so that you can describe it, which will help in your treatment.